When discussing Japanese paints, Aotake will inevitably come up. So what is Aotake? Aotake was a translucent blueish green coating used for interior surfaces on both army and navy aircraft.

Aotake finds it’s roots in urushi varnishes, lacquers made from the sap of the Toxicodendron vernicifluum, the Chinese lacquer tree. These forms of Aotake would be used for the protection of armour. ‘Modern’ Aotake was developed early 1930’s. For the army it was officially introduced on the 3rd of March 1932.

Similar in usage to the American zinc chromate, this Japanese enamel coating was of superior quality. It however remains a mysterious paints. Virtually forgotten after the war until the ’80, few intact samples remain after more than 75 years. Most salvaged aircraft were stripped of their original paints, and/or repainted.

Translation

The controversy of Aotake starts with the name. If you were to pull the word through google translate, the individual kanji would translate as “blue” (青, ao) and “bamboo” (竹, take). However, this translates to “Green Bamboo”, and not blue.

So what causes this discrepancy? The short answer is that historically, Japanese didn’t quite see blue and green as separate colours. But to make a short story long:

In English, the rainbow has seven colours. But colours are a spectrum, and when actually looking at said rainbow, there are no sharp lines, just a blur of colours smoothly transitioning into the next. Where the arbitrary lines between colours are placed, where a colour ends and where a new one starts, sometimes differs from language to language. For example Russian sees light and dark blue as two distinct colours; Голубой (Goluboj, light blue) and Синий (Sinij, darker blue).

In ancient time, Japanese didn’t have a distinction between blue and green, and both were called 青, ao. Later on, during the Heian period (794-1185) a distinct word for green was developed; 緑, midori. This however was still seen as a shade of aoi, 青, with the latter encompassing both colours. Similar to how in English crimson and maroon would still be seen as a shades of red.

The split to two separate colours didn’t happen until after the second world war (maybe due to globalization?) meaning WWII era ao, 青 would encompass the part of the colour spectrum that in English is referred as either blue or green. Even to this day certain green objects are still referred to as ao, 青 in modern Japanese, such as plants and and traffic lights. This is also the reason for the earlier mentioned translation difference. This means there is no correct translation of aotake, 青竹, as the English lexicon doesn’t have a word for a colour that encompasses the full range of WWII ao, 青 colour spectrum.

In some original Japanese documents the colour is also referred to as 青竹色, or aotakeshoku, where shoku, 色 means “colour”; blue green bamboo colour. It’s sometimes also written as 淡青色透明, thin translucent blue colour.

Colour

Aotake in as of itself is colourless, with pigments added to aid in creating an even, thick enough coating. It’s metallic sheen comes comes from the aluminium underneath.

As with most wartime primers and coating during the war, the exact shade wasn’t really important. Therefore there was no standardized amount of pigment added, and as a result, different variations of Aotake shade existed, ranging from the famous teal colour, to green and even brown.

The colour difference is sometimes suggested to be the result of the paint fading, as this was quite common among other paints. There is however very little concrete evidence to support this. On the contrary, samples show that exposed areas showed very little fading when compared to covered areas when examining surviving wrecks. That is not to say they would look exactly the same. Because new coatings of Aotake would be applied throughout the manufacturing process, even after assembly, the covered parts wouldn’t necessary look the same as the uncovered parts.

Application and Usage

The way Aotake was applied is different then western style primer application. Where the Americans for example applied their Zinc Chromate primer after assembly, the Japanese applied a layer Aotake after every step of the manufacturing process. When a part would be manufactured, it would receive a coat, and after assembly, it would for example receive a new coat. At the end there would be no metal visible

http://colesaircraft.blogspot.com

At the end of the manufacturing process, the plane would sometimes receive a matte black coating. The reason for this is unknown, it might have been further protection, or to reduce de glare of the Aotake.

http://colesaircraft.blogspot.com

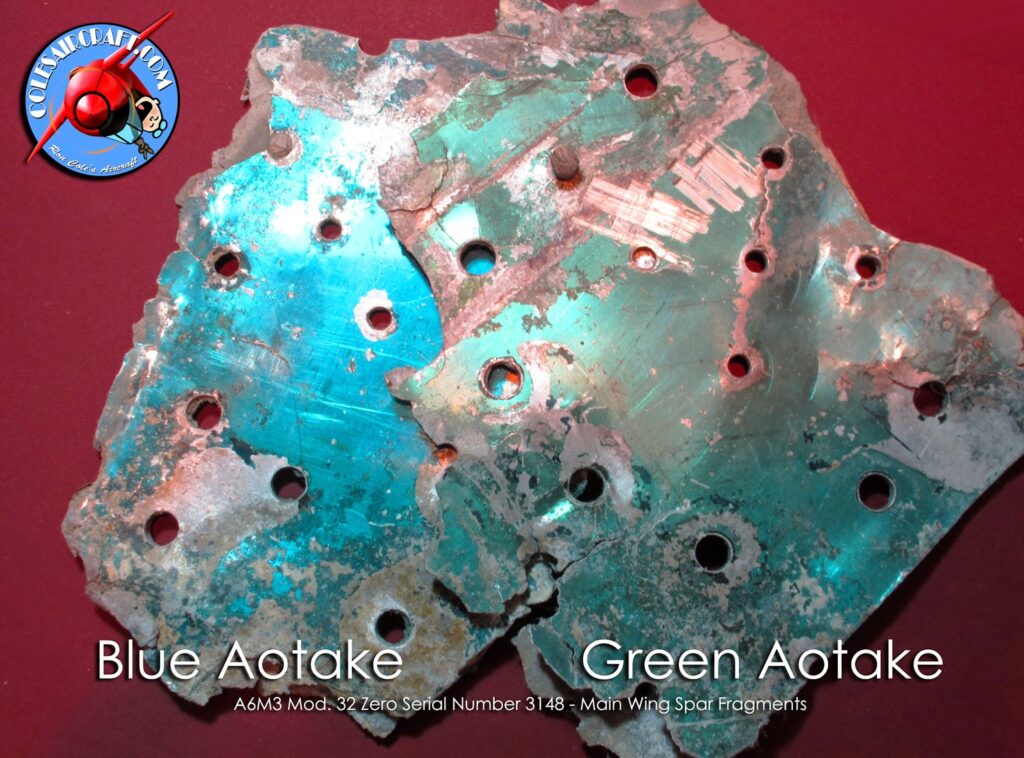

The Japanese aircraft industry was quite decentralized, especially in the later stages of the war to try to evade allied bombing. This sometimes resulted in different parts being produced at different locations by different subcontractors. These often had different batches of Aotake they used on their parts after their assembly. This resulted in aircraft often having a variety of different shades of Aotake. Below an example of two different shades of Aotake encountered on the main wing spar of a Zero.

As far as I’m aware, neither of these differences are accounted for with restored aircraft, which are painted with the ‘regular’ style of primer application; only after assembly. This results in a even, mono-colour Aotake layer, where in reality different parts would have different colours, with different amount of application.

Photo by Ron Cole, used with permission.

http://colesaircraft.blogspot.com

Reproduction

When painting Aotake as a modeller, there is no definitive Aotake colour, so don’t sweat about it. Use an Aluminium base and spray this over with translucent blue, green or a mix of the two and the result will most likely be correct. Personally I use a blend of Tamiya X-25 and X-23, in whatever ratio i fancy that day.

Much more important for the modeller with an eye for perfection is to use multiple shades of Aotake. make the landing legs more greenish while making the wheel bays bluer for example.

Sources & further reading

- Ishiguro, R., Januszewski, T., & Karnas, D. (2018). Japanese anti-submarine aircraft in the Pacific War. Sandomierz: Stratus sp.j.

- Mikesh, R. C. (2000). Japanese aircraft interiors, 1940-1945. Sturbridge, MA: Monogram Aviation Publications.

- Color identification Standard for Naval airplane –Temporary Specification No.117 Additional Volume.

- Japan Aircraft Standards No. 8606 Aircraft Paint color standard

- Research on Kariki 117 by Ryoichi Watanabe

http://angelof.web.fc2.com/subw117-1.htm - https://www.alternatewars.com/BBOW/Colors/Japanese_Aircraft_Colors_WWII.htm

- http://www.aviationofjapan.com/2019/12/army-prop-and-spinner-colours.html

- http://www.aviationofjapan.com/2008/04/j3-2-6.html

- https://plaza.rakuten.co.jp/zerosenochibo/diary/ctgylist/?ctgy=30

- http://www2.odn.ne.jp/~cdh88520/il2_1946_skin_color_index.html

- https://web.archive.org/web/20150727230123/http://maker-one.ddo.jp:8080/cdh88520/color_list_for_ww2fighters.html#c19

- https://roncole.net/blogs/ron-cole-coles-aircraft-aviation-art/12072261-japanese-world-war-ii-aircraft-aotake-paints

- http://colesaircraft.blogspot.com/2014/08/japanese-wwii-aircraft-aotake-primer.html

- http://www.aviationofjapan.com/2018/07/tom-halls-comment-associated-ideas.html

- https://giraku.com/2022-04-03 日本軍機迷彩塗装考その2~零戦の初期迷彩色/

- https://www.sohu.com/a/519095797_100140957

- http://www.j-aircraft.com/a6mresearch/accolors.htm

- https://plaza.rakuten.co.jp/satsukiyamazakur/diary/200807150000/

- https://ndlonline.ndl.go.jp/#!/detail/R300000001-I000007460147-00