This page is an article in a larger series about early Chinese aviation. Please read those for more context about the history of China at the time that led to the creation of the many factions.

Roundels

With the background out of the way, let’s look at the various roundels used over time by the various factions.

Chinese republic

Beiyang Roundel |

|||

| 1913-1920 | |||

Beiyang Star |

Beiyang Circle |

|

|

| Roundel | Rudder | Fin Flash | |

The Republic of China started it’s air force in 1913 with a dozen Caudron G.III planes. The roundels colours were based on the flag and represent the main ethnic groups: the Han (red), the Manchus (yellow), the Mongols (blue), the Hui (white) and the Tibetans (black). The air force broke up in 1920. Early On the star was used only on, but around 1919 this changed to to the flag on the rudder with the star painted on the usual sides.

Apparently near the end of the air force some planes were instead equipped with a circular roundel.

At times, the flag

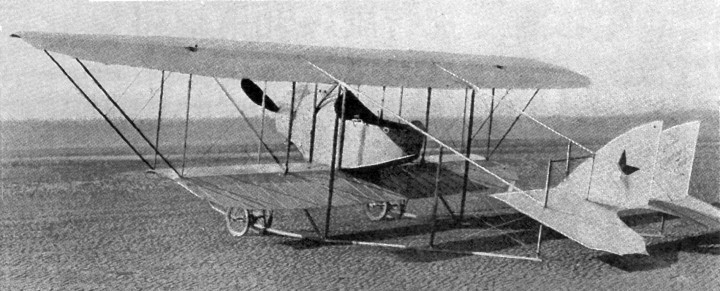

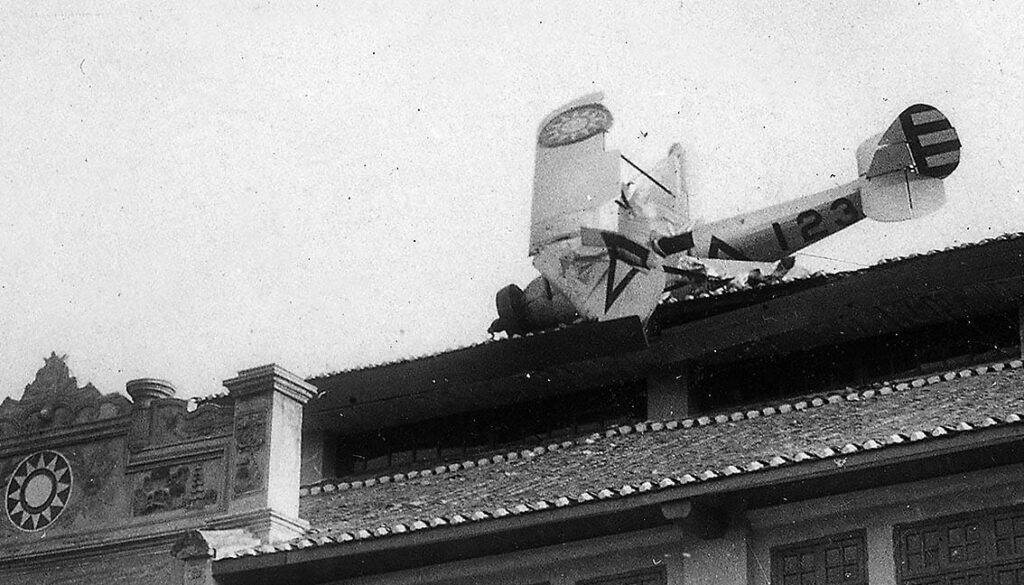

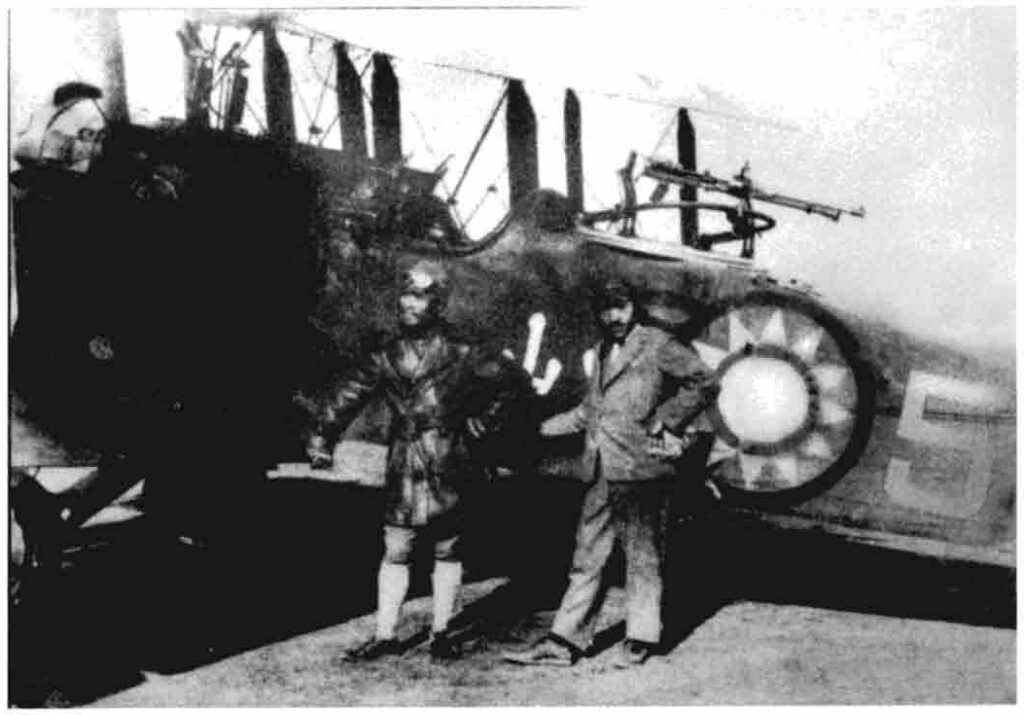

Caudron G.III planes of the Revolutionary government, adorned with the Beiyang star on

Provincial Air Forces

The various provincial air forces mostly used insignia based on the blue sun.

Guangxi Air Force

The New Guangxi (sometimes written Kwangsi) Clique came into power in the spring of 1924. Around 1928 it was reported that the province was about to set up an air force, with the first four aircraft arriving early 1930. The air force was inaugurated early 1932, with the force rapidly growing afterward with mostly British, but also French and Japanese aircraft.

After the Japanese invasion 1937, the Aeronautics Affairs commission in Nanking transferred all aircraft and personnel to the central government, putting in end to the last remaining independent air force in China.

| 1932-1937 | ||||

Qīngtīan Báirì |

Light background triangle |

Dark background triangle |

|

|

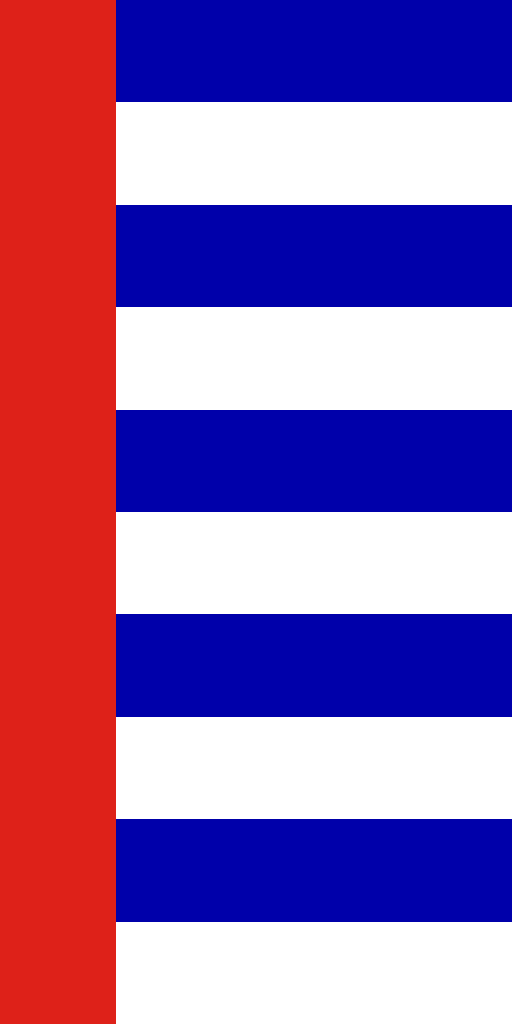

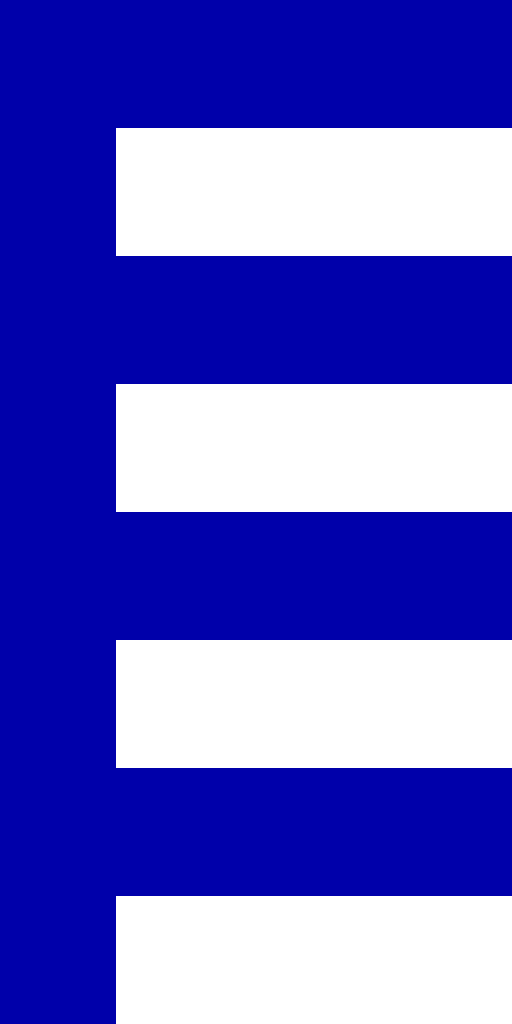

| Right Wing Roundel | Fuselage / Left Wing Roundel | Rudder | ||

| The fuselage was adorned with a Black and White upside down triangle. The colour order was determined by the undersurface, with a dark undersurface using a white bordered black triangle, and a lighter surface the black-bordered white triangle. Rarely the fuselage sides were painted by the Qīngtīan Báirì. The Wings had a triangle painted on the left wing, and the Qīngtīan Báirì on the right wing. The tail most of the time had the rudder painted with varying amounts of white-blue stripes, with a single vertical stripe. It isn’t clear from p |

||||

hotographs whether this stripe was red or blue, of might have been both. Sometimes the tail was adorned with the Qīngtīan Báirì instead.

Canton Air Force

After Sun Yat-sen’s return to Canton from Japan in 1917 where he started his own military junta

| Bureau of Aviation |

|

| 1923? – ? | |

Qīngtīan Báirì |

Bureau Seal |

| Roundel |

Fin Flash |

| At least three aircraft, the “Rosamonde” and two Curtiss N-9C were outfitted with the logo of Canton’s Bureau of Aviation. It reads 局空航, Hángkōng jú on top, and 造月六年二十國民, Mínguó shí’èr nián liù yuè zào on the bottom. These can be translated as “Aviation Bureau” and “Made in June of the twelfth year of the Republic of China” respectively. Note that the pinjin are read right-to-left. Current day this would be thus be written 航空局 and 民國十二年六月造 respectively. This text is read from the Rosamonde, with the date referring to the construction date of that plane. The text on the Curtisses may read something else, but the photo is not high enough resolution to verify. The fuselage sides of these aircraft don’t appear to have any roundels. Qīngtīan Báirì roundels were placed at least on the top of the wings of the N-9C, and a modern reproduction of the Rosamonde shows the white suns on both the top and bottom of the wings. |

|

| 1st Cantonese Air force / Chung Shan Aviation Team | |||

| 1921-1927 | |||

Qīngtīan Báirì |

中山 |

山中 |

None |

| Roundel | Right Fuselage | Left Fuselage | Rudder |

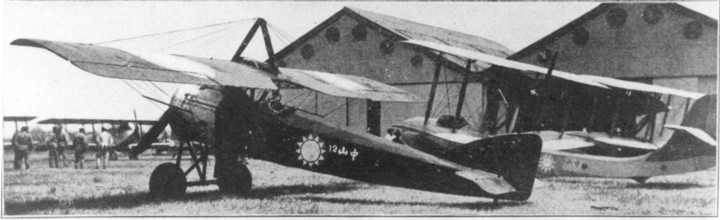

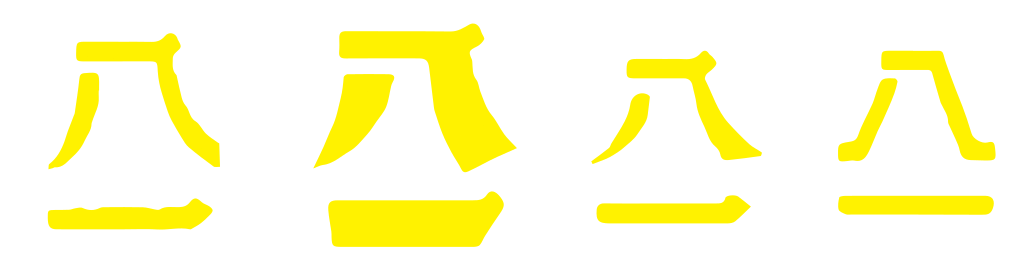

| These aircraft had “中山”, Zhōngshān painted on the side, after President Sun Yat-sen, who had multiple names and whose most popular Chinese name was Sūn Zhōngshān, derived from his pseudonym in Japan. This is sometimes romanized as Chung Shan.B oth are used at times in sources, but I’ve decided to read and transliterate it as Zhōngshān, the transliteration of Sun’s name. Noted, contemporary horizontal chinese texts were mostly written right-to-left, but in special circumstances written left-to-right. One of those is text on vehicles (such as aircraft) where text is written and read front to back. This also leads to the fact that in both sides the text is backwards; Shan Chung / Shānzhōng. I’m not so versed in Chinese text culturally what the reason of this would be, and how is should be read. |

|||

Japanese Puppet states

Manchuria

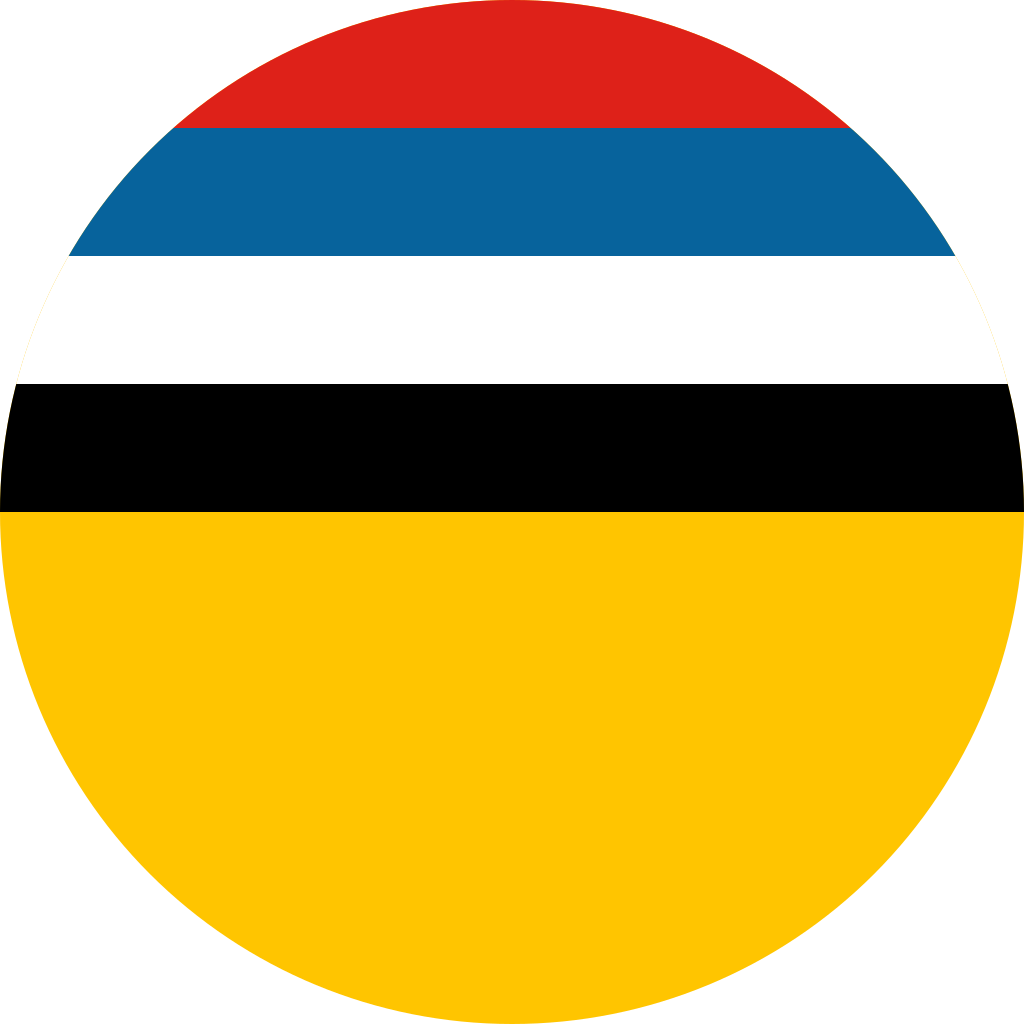

| Manchukuo Imperial Air Force |

|

| 1937-1945 | |

|

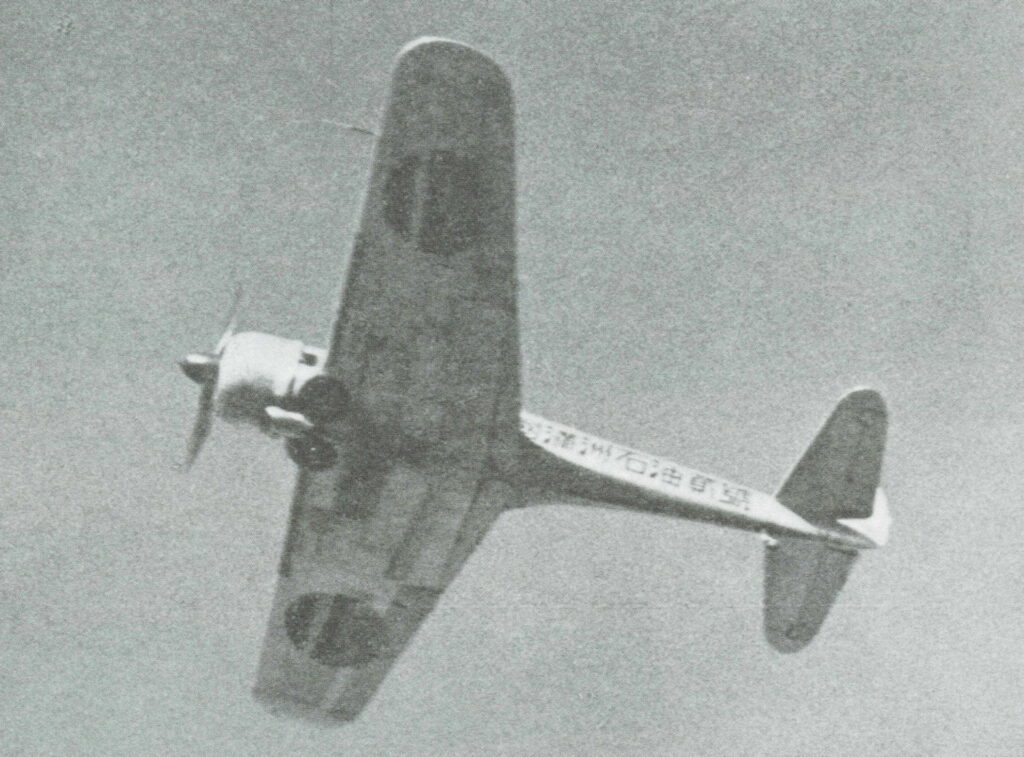

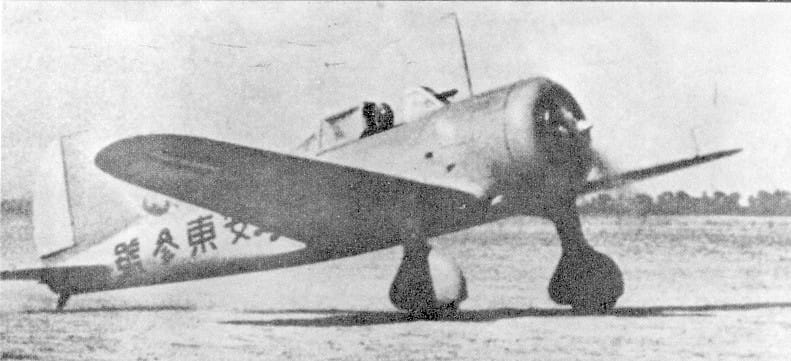

Example of a donation text, 護國滿洲石油壹號 |

| Wing Roundel | Fuselage donation message |

| The roundel of the Manchukuo air force was based on it’s flag and was only applied to the top and bottom side of the wings. One detail that is often missed is that on the Ki-43’s the lines between the colours weren’t parallel, but followed the rivet lines. Aircraft (or money for it) was donated by local companies, and the plane bought or donated had a donation message on the fuselage. This message was to be read from front to rear, meaning the message was mirrored on both sides of the plane. The message contained a motivational phrase, such as Protecting the Country!, the name of the company and the number of the plane |

|

| Known Donation Texts | ||

|---|---|---|

| Nakajima Ki-43-II Hayabusa | ||

| 護國滿洲石油壹號 Protecting the Country, Manchuria Petroleum Company, No. 1 |

Left |  |

| Right |  |

|

| 護國滿洲石油貳號 Protecting the Country, Manchuria Petroleum Company, No. 2 |

Left side | 護國滿洲石油貳號 |

| Right side | 號貳油石洲滿國護 | |

| 護國勞貳壹第報號 No. 21 of the National Defense Service |

Left side | 護國勞貳壹第報號 |

| Right side | 號報第壹貳勞國護 | |

| 護國龍江縣壹號 Protecting the Country, Longjiang County, No. 1 |

Left side | 護國龍江縣壹號 |

| Right side | 號壹縣江龍國護 | |

| 護國松花江勤奉號 Protect the Country! From the Labour service group of the Songhua River |

Left side | 護國松花江勤奉號 |

| Right side | 號奉勤江花松國護 | |

| 護國松花江第報號 Protect the Country, |

Left side | 護國松花江第報號 |

| Right side | 號報第江花松國護 | |

| Manshu Kokuyusho Kabushiki Kaisha Manchuria Air Transport Company |

|

| 1931-1945 | |

|

|

| Wing Roundel | Fin flash |

| The MKKK was a paramilitary airline, whose primary function was to provide liaison services to the Manchukuo military and government. Although civilians were also carried, this was a lower priority. | |

Mengjiang

A Manshū Super Universal (A copy of the Nakajima Ki-6, which in turn was a licence built version of the Fokker Super Universal) was gifted to Prince Demchugdongrub (Also known as Prince Teh Wang) in 1935 by Manchukuo, likely as a means of aiding him with setting up an autonomous Inner Mongolian government at the time, which would become the puppet state of Mengjiang.

| Inner Mongolian Army |

| 1935 – ? |

|

| Roundel |

| Although i haven’t been able to find photographic evidence of this plane, apparently this roundel was placed on the upper and lower wings, and the tail surface. The side of the fuselage had the text written: “Inner Mongolia Army No.1 – Heavenly Horse” in old Mongolian script. |

People’s Republic of China

Northeastern Democratic Alliance Aviation School

After the defeat of the Japanese in 1945, the Communist rushed to seize the Japanese held territories, with Soviet support. The Northeast People’s Autonomous Army Aviation Corps was established on January 1st 1946, with The North East Old Aviation School as the first true aviation school of the Chinese Communist Party. It was established in Tonghua, but moved around quite a lot during it’s early years.

| Qīngtīan Báirì | |

| 1946-1947 | |

|

|

| Roundel |

Fin Flash |

| Early on, the aviation school used the same roundel and fin flashes as has been used by most Chinese factions. | |

| 中 star |

|

| 1947-1949 | |

|

Qīngtīan Báirì |

| Roundel |

Rudder |

| Starting 1947, aircraft started to be repainted with a new roundel consisting of the Chinese national emblem 中 embedded in a communist 5-pointed star. | |

Our aviation school’s aircraft have recently been flying frequently between Dong’an and Qianzhen. For easy identification, we have specially designated a red five-pointed star with the word “Zhong” in the middle (all red) as the aircraft symbol of the school. We hope that all our troops will pay attention to identification and avoid misunderstanding. We hereby inform you.”

May 7 1947, Notice by the Eastern General Headquarters

Peoples Liberation Army Air Force

The hànzì in the middle of the roundel read 八一, translating to 8 and 1, referring the august the 1st, the date of the Nanchang Uprising.

| 1949 August 1st Roundel |

|

| 1949 – 1997 | |

|

|

| Roundel |

八一 fonts |

| In 1948, China started the process of unifying it’s military emblems, including it’s aviation roundel. On June 15, a new directive for the roundel was issued. The font of 八一 wasn’t specified until 1958, with the text “August 8th” appearing in many ways. The emblem was slightly updated in 1997 | |

| Shenyang J-8 August 1st Roundel |

| 1980- 2003 |

|

| Roundel |

| The Shenyang J-8 had it’s own variation of the roundel using fully trimmed wings. It was not until 2003 that they were gradually changed to the regular emblem |

| 901A-1997 August 1st Roundel |

|

| 2003 – current | |

|

|

| Roundel |

Low-Visibility Roundel |

| In 1997 a new standard, 901A-1997, was introduced which redefined the aircraft emblem. It would take until 2003 for the emblem to appear on new aircraft. | |

Thanks, I have spent hours trying to research Chinese roundels and you have put it all here. Great job

Hi, thanks again for an excellent blog. I have come across a roundel that is said to have been used on captured Japanese fighters by the PLA but have not found any proof of such. A white trimmed black outlined red star with a white China symbol on the inside. Have you come across this?

You mean this one: https://emmasplanes.com/wp-content/uploads/information/camouflages/China/PLAAF_Roundel_1946-1949_Ki.png?

As far as I’m aware, this was used shortly after the war on trainers, mainly Ki-79 but allegedly also the Nanchang CJ-5 and Shenyang X-10 (license build SZD-8) gilder. However I’ve found no high-resolution images yet. To actually confirm (only a super low-res of the X-10 that shows a dark star at most)